Remembrance Mural at Rowlatts Mead Primary Academy, Leicester

Sept – Oct 19

‘When I am laid, am laid in earth, may my wrongs create

No trouble, no trouble in thy breast;

Remember me, remember me, but ah! forget my fate.

Remember me, but ah! forget my fate’. (Dido’s Lament – Henry Purcell)

Same place, but with a new name. Since my previous visit to Rowlatts Hill the school has now become Rowlatts Mead Primary Academy, but other than the change of logo nothing looks changed.

It was a swift return, having been only a short time since the completion of the Rainforest/Under The Sea themed corridor but in truth this project was actually an unfinished element of that previous visit. I had left in order to fulfil a promise of completing a painting at Meadowside Primary in Burton Latimer before the end of their summer term, but with an assurance that I’d return immediately afterwards so that this one would be finished before November.

The completion date of this project was critical as the subject I’d been asked to illustrate was the theme of Remembrance. It was a significant challenge and a subject I’d been faced with a few years ago, at Warmington School, but this was different and the design posed a succession of difficult decisions and dilemmas.

The location identified was the entrance and reception area of the school, the first impression to any visitor, therefore it was important that the appearance of this very serious subject was given the sobriety and gravitas it deserved. Any memorial to the fallen has an air of solemnity however I was determined it would appear neither clichéd or dour. The visual language of the composition needed to convey a dignified presence, incorporate a recognition of activity both past and present in the theatre of war but also that the sacrifice made has been in order for the world to be a better place.

I devote many hours to the design stage of any project. Being a fixed and permanent feature on a wall the painting of a mural is a tremendous responsibility. It’s a big investment and located in a public space, it’s so important to get it right.

The easy option would have been to paint a mournful memorial with a subdued palette, but the end result would have been predictable, unimaginative and dull. Fortunately I don’t work that way. My priority is always to create a stimulating image with underlying stories to investigate. I felt more was possible. In my mind’s eye I could see something brighter.

I preferred to approach the subject through the eyes of an Impressionist and present a contemplative landscape, as well as implementing the full spectrum of colours. A hostile critic once famously characterised Impressionism as, ‘the crude application of paint, the down to earth subjects, the appearance of spontaneity, the conscious incoherence, the bold colours, the contempt for form’. I feel this description identifies my painting technique perfectly.

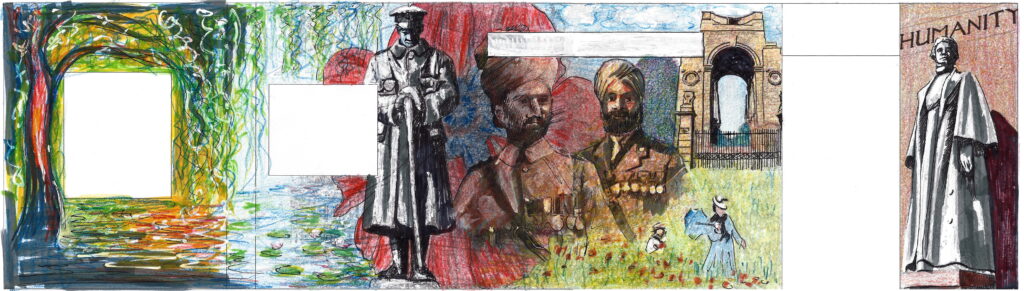

The allocated space had four definite divisions. First, a self-contained vestibule; Second, a short wall which then turns into a corridor; Third, the corridor wall itself; Fourth, the wall between two office doors.

It was a significant problem to overcome. Not only to find a way of piecing together a design that flowed and linked naturally across four sections with built-in barriers, such as doors, a 90º corner and window frames, but also one that could be enjoyed as a painting in itself, and able to successfully communicate a serious underlying message.

Following several unsuccessful attempts the composition I eventually settled upon to present at a design meeting at the school was well received. Only one alteration was requested, that being the replacement of one of the historical figures for a contemporary one. (My original design included Subedar Major Thakur Singh Bahadur of the 47th Sikhs, who was among the first to receive the Military Cross for gallantry in action on October 27, 1914 at Neuve Chapelle).

My predominant influence and inspiration was the late work of Claude Monet. In particular, that which led toward and included his last great masterpiece, the Grandes Décorations for the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris.

The painting begins with an image based upon one of Monet’s Saule Pleurer (Weeping Willow) series of paintings, and the theme of his garden in Giverny continues to include two interpretations of the Water Lily pond. There is no horizon, simply a reflection of sky on the surface of still water.

At the corner, where the wall turns into the corridor, a solemn statue of a soldier stands in front of a monumental poppy based upon a painting by Georgia O’Keeffe.

Another painting by Claude Monet, his Coquelicots (Poppy Field), forms the basis of the composition on the corridor wall and the admin office door, towering over which stands a landmark of local interest, the Arch of Remembrance in Victoria Park, Leicester. Two military portraits emerge from this landscape, the first a contemporary figure, Lance Corporal Michelle Norris MC, the second an historical one representing Asian involvement with the British Army, Khudadad Khan VC.

The final figure which completes the design is one that illustrates the caring side of conflict, that of nurse Edith Cavell.

(A more detailed commentary of all of the design elements can be found at the foot of this blog).

The elements in detail:

Claude Monet – Weeping Willow 1918 (Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio)

Monet painted a series of 10 paintings depicting this majestic tree growing beside the lily pond in his Giverny garden. Painted toward the end of the First World War the tree has great significance, it is a symbol of sorrow, as a lamentation on the state of the world. French deaths in WW1 totalled over 1.4 million with 4 million wounded, a quarter of all French men born in the 1890’s had been wiped out.

These paintings were an expression of grief, Weeping Willows were seen a symbol of death and mourning, a common sight in French cemeteries and often personified as a woman or used to symbolise female mourning. The tree was the subject of ‘Élégie’, one of the prose poems by JJ Grandville in his book Les Fleurs Animées (Flowers Personified) published in 1847. “Come into my shade all you who suffer, for I am the Weeping Willow. I conceal in my foliage a woman with a gentle face. Her blond hair hangs over her brow and veils her tearful eye. She is the muse of all those who have loved…….She comforts those touched by death”.

Claude Monet – The Water Lilies: Clear Morning with Willows 1915 – 1926 (Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris)

The vertically structured Weeping Willow paintings were ultimately overtaken by the expansive horizontal format of his final monumental Water Lily series. In these he dispensed with the horizon completely to focus solely on the reflections of the sky, the surface of the water, the flowers and lily pads floating in a world seen upside down. This series known in English as the Water Lilies is a translation of the French word Nymphéas, which is related to Nymphes (Nymphs), female spirits who live in sacred places. The water lily is closely related to the lotus which the Egyptians identified as a symbol of birth and immortality, while in Buddhist and Hindu philosophy it represents the mind rising up from the mud and opening itself to wisdom and enlightenment.

A collection of these great paintings were eventually donated to the state and are now permanently housed in the Musée l’Orangerie in Paris. They fill two large oval rooms, a collection which Monet hoped would offer beauty to wounded souls, calm nerves and offer the viewer ‘an asylum of peaceful meditation’. He felt his late paintings were an attempt at healing – his artistic response to the traumatic events of the war. They were intended as an invitation to sit and observe the painted reflections in the water as one might the continual turn of waves on a seashore, or the flames of a living room fire.

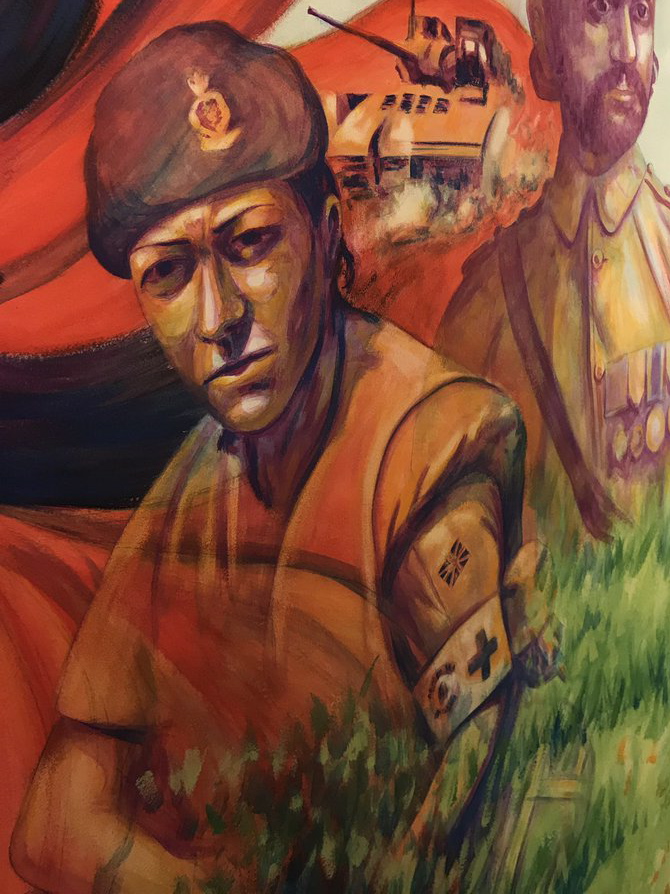

Ambrose Neale – Serviceman from London and North Western Railway War Memorial 1921 (Euston Station, London – Memorial designed by Reginald Wynn Owen)

The central figure is derived from one of the four bronze figures representing an infantryman, artilleryman, sailor and airman, located on each corner of this memorial. He stands, head bowed, hands resting on an upturned rifle, which is reversed in mourning.

Georgia O’Keeffe – Red Poppy VI 1928 (Private Collection)

“Nobody sees a flower really; it is so small. We haven’t time, and to see takes time – like to have a friend takes time”.

“So I said to myself, I’ll paint what I see, what the flower is to me, but I’ll paint it big and they will be surprised into taking time to look at it. I will make even busy New Yorkers take time to see what I see of flowers”.

“When you take a flower in your hand and really look at it, it’s your world for the moment. I want to give that world to someone else. Most people in the city rush around so, they have no time to look at a flower. I want them to see it whether they want to or not”.

“I decided that if I could paint that flower in a huge scale, you could not ignore its beauty”. (Quotes by Georgia O’Keeffe)

Claude Monet – Coquelicots (Poppy Field) 1873 (Musée d’Orsay, Paris)

A field strewn with poppies continues Monet’s presence and influence of the composition. Although having no connection with the theme of war, I felt nonetheless it was an appropriate choice. It continues the Impressionist theme around the turn of the wall into the corridor and implies an atmosphere of loss and melancholy. A young family walks through a poppy filled landscape, the father figure is absent.

Lance Corporal Michelle Norris MC

Private Norris was just 19 when she was recognised for her bravery for her actions during the war in Iraq in 2006 and became the first woman ever to receive the Military Cross. I selected this portrait to replace that of Subedar Major Thakur Singh Bahadur, MC which featured in my original design.

At the age of 26 Sepoy Khudadad Khan was the first native-born Indian to be awarded the Victoria Cross. His bravery was also the subject of a play, ‘Wipers’ by Ishy Din, performed at Leicester’s Curve Theatre in 2016. It was written to ‘honour the contribution of the million South Asian soldiers who fought alongside their British brothers during the First World War’.

Sir Edwin Lutyens – Arch of Remembrance 1925 (Victoria Park, Leicester)

A recognisable and identifiable local landmark, the arch is situated on the highest point of Victoria Park. Designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens an inscription above the north-east arch reads: REMEMBER IN GRATITUDE TWELVE THOUSAND MEN OF THIS CITY AND COUNTY WHO FOUGHT AND DIED FOR FREEDOM. REMEMBER ALL WHO SERVED AND STROVE AND THOSE WHO PATIENTLY ENDURED

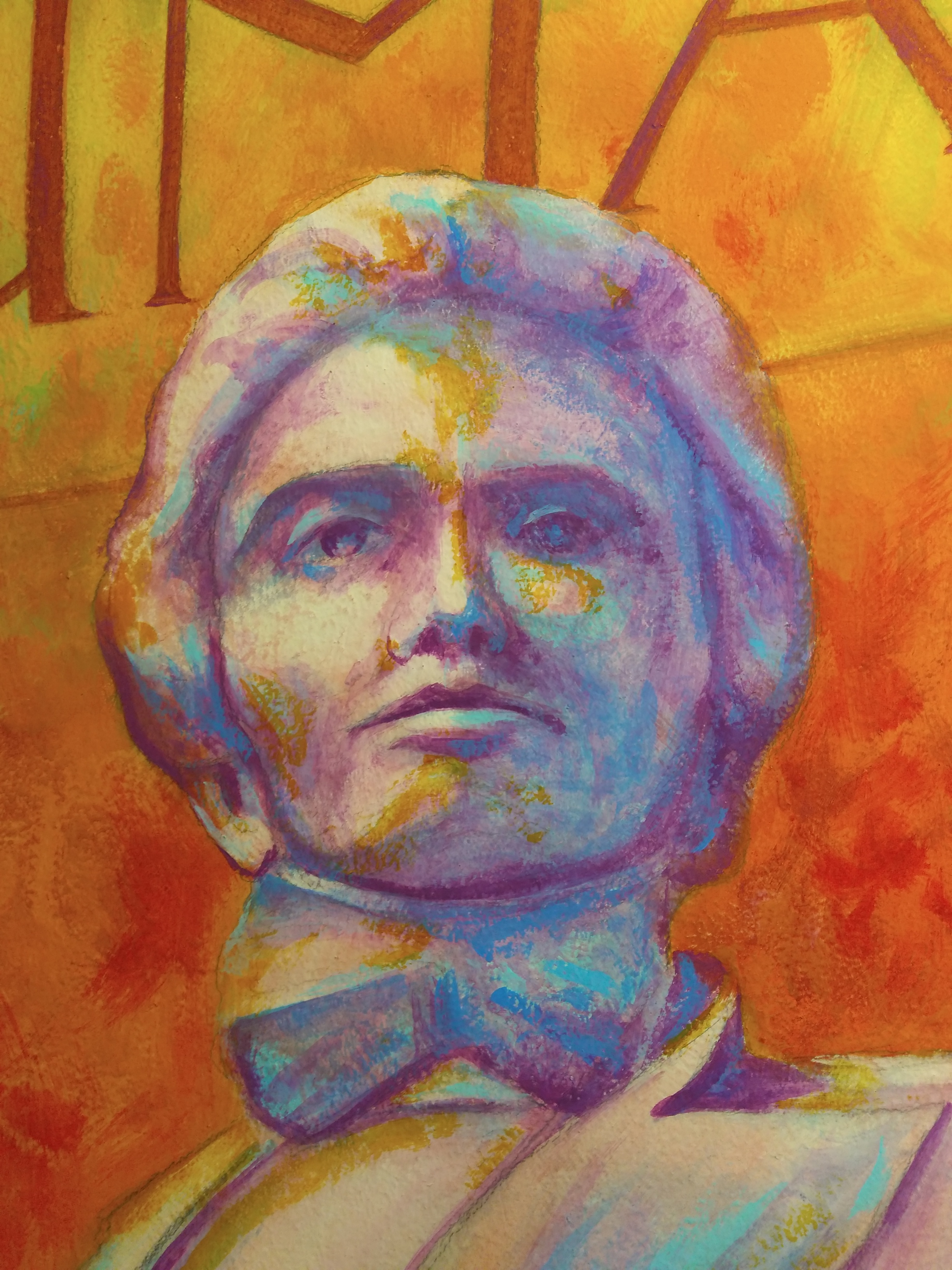

Sir George Frampton – Edith Cavell Memorial 1920 (St Martin’s Place, London)

The final element of the composition is a portrait of Edith Cavell, a British nurse working in German-occupied Belgium during the First World War and celebrated for saving the lives of soldiers from both sides without discrimination. She also helped British, French and Belgian soldiers escape by arranging for guides to smuggle them out of Belgium into the neutral Netherlands. For this she was arrested, tried and found guilty of ‘assisting men to the enemy’ and executed by a German firing squad on 12th October 1915.

Rowlatts Mead Primary Academy, Balderstone Close, Leicester LE5 4ES

Leave a Reply